The service was beautiful. We were able to connect with Father Dann from the Church of the Advent in Madison, GA and who leads the congregation at the UGA student Episcopal Center. He was able to craft a unique and personal service that included some of my dad's favorite hymns: Lift High the Cross and All Things Bright and Beautiful. We closed the service by singing Brahm's Lullaby in German - one of my dad's favorites from the last few months.

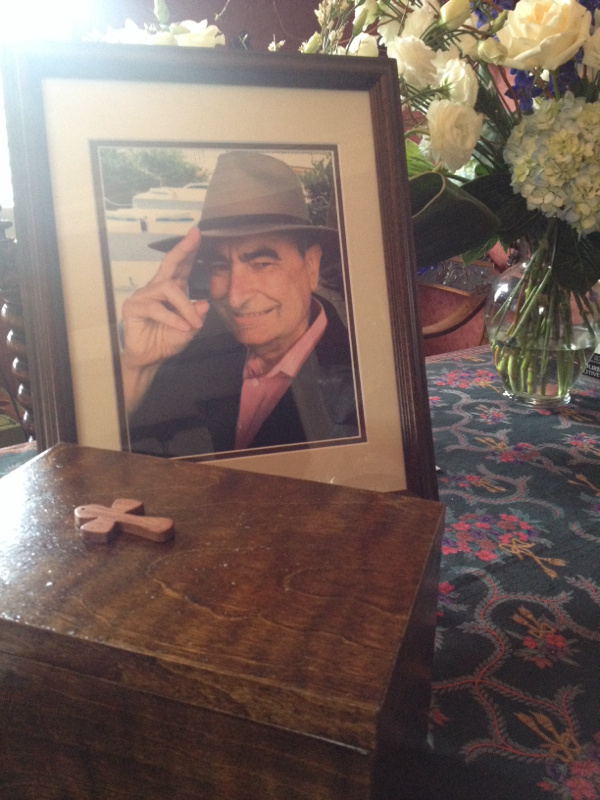

My husband Chris made the urn for my dad's ashes (pictured above). My dad asked him to do it several months ago and Chris had many ideas for it including making it out of teak, a favorite of my father's, and teaching himself how to turn on a lathe. Typical to my dad however, he had his own ideas: a box made out of 3/4 inch plywood and measuring 10 x 6.5 x 7 with a cross on top. With the help of Charlie Wooten's woodshop, it turned out lovely and is correctly made for the Green burial requirements setup by Honey Creek Woodlands; His final resting place at the Monastary of the Holy Cross in Conyers, GA.

My sister Margaret and my Aunt Elisabeth (my dad's sister) both gave beautiful eulogies to the memory of my dad. I will post both here along with the program from the service so that those of you not in attendance can feel the tone of the service. It was one of love and remembrance and friends and celebration and it was perfect. My dad would have loved it.

Eulogy By Margaret Goerig

He was a worldly man, my dad. Before he could even walk very well, he was on the go. Granted his first journey was not a happy one, nor was it his choice; he was a toddler and already a refugee, being carried in the arms of his oldest sister to get from the Sudetenland, where he was born, to Germany, where he would be raised. Maybe that’s why, as long as I knew him, he seemed to be a willing pilgrim, going wherever he was called as if he was being by carried.

Some great force eventually brought him to the United States, where he had a few adventures, before he finally met my mom, married her and had my sister and me. Even then he did not stop moving. His job called him across the country often but because he was a family man, he always took one or all of us with him in some way— be it an invitation to join him for the week, or by bringing a souvenir home to prove that he was thinking of us somewhere between the airport and his hotel room.

I eventually grew old enough to begin wandering the world myself, and so the first place I went was Wyoming, the summer I turned eighteen. Then it was California. Then I made a temporary return to Georgia but not without living for a semester in Toronto, Canada. Then I moved to Virginia, and later Spain, before Mexico, before a huge continental road trip that finally ended with me in California again, where I live now. It was a fifteen-year cycle to get back to where I had started and he was beside me many steps of the way. He and my mom helped me move at least half those times, but I cannot count all the boxes they packed and unpacked, and then later repacked, nor how many fans and lights my dad assembled and hung, only to later take them down and disassemble them again, nor all the miles they drove together with my stupid stuff in tow. Then, once I was settled, he always came to see me on multiple occasions— sometimes with my mom, sometimes alone, but always willing.

***

The diagnosis of his tumor came just a few weeks after his last trip out to see me. He and my mom had grown tired of all my boxes that I had been blatantly stashing in their basement and attic for about a decade, and so they jumped on a sliver of time in the fall, just before winter would cast its white, impassable blanket all across the mountains that separated us. They rented a U-Haul, drove the nearly three thousand miles to reach me, delivered all my things with their usual good-humored smiles, and stayed just long enough to be perfect house guests. Then they were on their way again, back to their home, where a fourteen-month struggle was awaiting all of us.

In the e-mail that my dad sent after his first MRI, he sounded dazed. We were all dazed. He had already battled prostate cancer years beforehand, and he was still contending with kidney failure, showing so much character and strength in the way he was tackling his dialysis; it was simply unfair to ask him to fight a brain tumor. And it was not just any brain tumor, either; it was the worst kind— the sort of killer in the night, who has found all the doors and windows locked, and thus dug in from under the foundation, up through the floorboards, slashing his way through every room in his path. The options to stop it were no less brutal: drilling into his head; leaving him wounded and confused; dripping poisonous fluids into his veins and making him sit under torturous beams of light, barely breathing through a hideous plastic mask that resembled something from a horror film.

In the end, these options would only buy time. But my dad took the deal. In his usual way, he was willing to embark on this voyage he had been called upon to make, and anyone who has read his blog knows that he was scared; he was unsure but he was also brave and I never saw him look back.

***

I have said a lot of goodbyes in my life. I have lived a lot of places and known a lot of people, and so farewells become part of that territory. I have never grown to like them, however, and my least favorite has always been the sort where I am the one to stay behind. It does not matter what beautiful landscape has surrounded me at the time; it does not matter if the parting is temporary, for the rule has never wavered: it is always easier to be the one who leaves.

I know the moments that follow a person’s departure well: there is a palpable ache as the silence settles into the empty space between the walls. That can go on for awhile but at some point, regular routine must make its return; there are dishes from the previous night’s bon voyage dinner, or sheets to strip from the guest bed, or trash to empty and appointments to keep and shopping to do. But in the midst of all those distractions, there is always some amount of consciousness that the person who has left is suspended between the point of departure and the point of arrival, and there will be a great moment of relaxation, when the message arrives that they indeed made it to wherever they were going, but until then, there is just a dull awareness of the passage of time and then an impulsive moment of looking at the clock and thinking: “I wonder if they’re there yet.”

***

When my father passed, we were all in the house with him. My mom was one bed over, taking a nap, and I was one room over, dozing, and my sister was yet another room over, knitting, while my brother-in-law was in the basement, building the box for the ashes after the cremation. You could hear my father breathing in almost every corner. It was labored and it was determined and it was hard to listen to, but he was giving it his final all. Then it stopped and I snapped out of my drowse. So did my mother, so that by the time his chest had gone still and everything around him was quiet, we were all gathered by his side, feeling the warmth slowly ebb from his body.

We stayed there for awhile, talking to him, stroking him, letting it sink in that after all this, it was over. After all the caregiving from my mother and sister and aunts and uncles and nurses, and after all the cheering on the sidelines from the rest of his family and friends, and after all the visits to the doctors and the hospitals, and after all the medicine and the praying and the wishing and the phoning and the writing and the handholding and the struggling— after all of that, he was gone; he had left.

***

We trickled out of the room eventually. We puttered around. We tried to figure out who to tell and what to do and where to be and how to act. Then gradually, we made our way back to his side. And we stared, because he looked different. His mouth had been gaping in his last gasp and his eyes had been cracked open ever so slightly and his chest had been tilted up a little, as if that was where the life had been pulled right out of him.

But at some point, that had changed, so that now his eyes were calmly shut and his torso was relaxed and his mouth was closed, the lips lightly pressed together with one corner turned up in a serene little half smile.

We looked at one another, asking did you do that? No, I didn’t do that; I wasn’t even here.

***

He had not been gone long enough for the question to even begin to work its way into my mind but it never needed to. I could tell by looking at him— we could all tell by looking at him that yes, he had indeed made it to where he was going.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed